Kenyans go to the polls tomorrow to elect a new president. Susanne Mueller explains the political dynamics at play. Jane (Mango) Angar and Kathleen Klaus outline the race and its implications.

Both leading candidates are well known: Long-time political activist turned politician Raila Odinga is running for the fifth time. He has the endorsement of current president Uhuru Kenyatta. It is his “Grand Finale.”

William Ruto is the current Deputy President, but is claiming that he is an outsider to the political establishment. He pits the race as one of “hustlers versus dynasties,” signifying Kenya’s new class politics. Learn more about Ruto’s “Grand Hustle.”

Nine years ago (I’m getting old!) I wrote a post for African Arguments where I outlined “Five simple points to take away from the 2013 Kenyan elections.” I revisit these five points with an eye toward tomorrow’s election.

Politics is more than elections

The 2013 election took place in the aftermath of Kenya’s deadly 2007-8 post-election violence. The atmosphere in the country was tense, and analysts worried that large-scale violence could break out. The election was mostly peaceful, and I concluded: “What this election has demonstrated is that comparing elections without looking at the process and politics of what happens between obscures more than it explains.”

Nanjala Nyabola goes so far as to say that we need to move beyond the focus on campaigns: “Democracy has become hollowed out into the performative act of voting, and not the hard and boring work of building societies that make sense for the people who live within them.” Elections are processes, not fixed events.

A lot has happened since Kenya’s 2017 election, as Duncan Omanga outlines. There was a massive shift in elite coalitions. A famous handshake between longtime rivals Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga in 2018 redrew the electoral math, splitting up the alliance between Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto. There is no Kikuyu candidate running for the first time since 1963. Ethnicity might matter less for these reasons, even though youth voters still feel trapped by it.

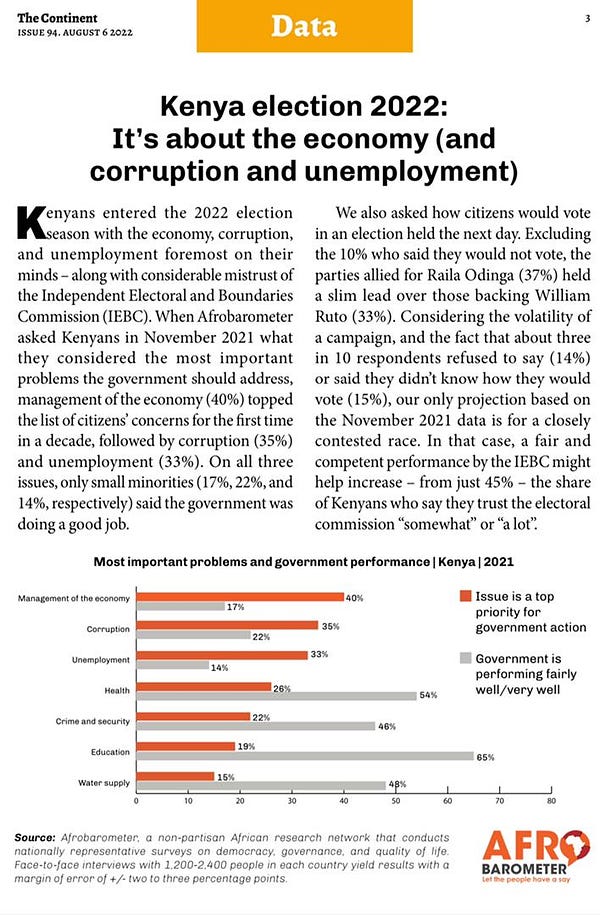

Inflation is up, food prices are high, a drought devastates the north, and Kenya owes huge amounts of debt to China. These issues are illustrated by the situation surrounding the Standard Gauge Railway, a “Jewel in the Crown of Corruption.” Kenyans observe a failing government. These charts explain where Kenya is today.

It’s the campaign, stupid

In 2013, Kenyatta outworked and outcampaigned Odinga. I wrote that Kenyatta ran a well-oiled machine; Odinga seemed exhausted and out of touch. Campaigning is crucial because Kenyan election campaigns are spectacles. And super expensive. The crowds are massive.

Political billboards engulf the nation.

Jeremy Horowitz’s Multiethnic Democracy: The Logic of Elections and Policymaking in Kenya sheds new light on where Kenyan politicians target campaigns, arguing that they spend lots of time and resources trying to win over swing voters. He concludes that this can encourage broad-based policy reforms and programmatic politics.

Amina Ahmed, Elfversson and Kristine Höglund draw attention to the important role that women are playing in the 2022 campaigns. Most important is Odinga’s running mate Martha Karua, who is the first running mate of a major party. She could help galvanize the urban vote.

Who is winning the campaign battle in 2022? While Odinga has the endorsement of Kenyatta, Ruto is proving to be the workhorse on the campaign trail that he has proven to be as Deputy the past nine years. Ruto has made significant inroads in Mount Kenya and Nakuru County. The winner of the turnout battle will be the victor.

The future is local

Kenyans are feeling the effects of devolution. County representatives, women’s representatives, senators, and governor races are hotly contested. Ken Opalo convincingly shows how devolution reshapes citizens’ sense of responsibility, creating new sources of political accountability. Waikwa Wanyoike argues that the real power is with the MP.

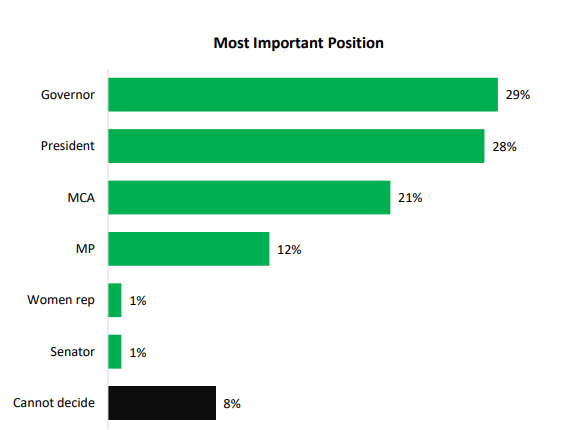

National candidates often build their followings at the grassroots, and then climb the political ladder. Challengers for the Governor race in Nairobi are even cleaning toilets and chopping vegetables to demonstrate they are men of the people. In a recent poll, Kenyans noted that the governor position is even more important than the president.

Yet devolution also reinforces the status quo. Subnational candidates have the chance to support or thwart important reforms, like land laws and distribution. The returns are not all rosy, as clientelism is formalized and more candidates have the chance to “eat” state resources. Despite decentralization efforts, politicians do not always target the poor, as GLD fellow J. Andrew Harris and Daniel Posner find in this new paper.

The collective capacity to get things done

In 2013, I wrote that “Kenyans demonstrated that democracy is more than a mechanism for counting votes, but rather a means of doing things together.”

Collective action at the grassroots is especially important for maintaining peace in neighborhoods and villages during contentious elections. Local peacebuilding efforts contribute to building resilience. Emma Elfversson finds that mediation and dialogue can yield peaceful solutions to local conflicts. This is especially important because elections can provide the opening for ordinary people to participate in violence. Women are at the forefront of many of these local peace efforts.

Community-level factors also help explain how voters respond to campaign activity—like vote-buying. GLD researchers Prisca Jöst and Ellen Lust find that local communities respond differently to election handouts, which are ubiquitous in Kenyan election campaigns. They draw attention to the social density of local neighborhoods—the extent to which residents know one another. People in high density neighborhoods are more skeptical of politicians, and do not expect handouts from politicians to make a difference in their lives. Voter responses to vote-buying might be shaped by the contextual factors of where they live.

Understanding Kenya’s democracy requires zooming in on what is happening at the grassroots in everyday life.

Land, livelihood, and interests

The election is about class and the economy, but there is not a single issue that defines it. For example, the land question is not front and center as it has been in past elections. While land grievances played a central role in violent mobilization in 2007-8, as Klaus documents in Political Violence in Kenya: Land, Elections, Claim-Making, they are less likely to serve as a collective action frame in tomorrow’s polls.

But as Mueller has demonstrated in her work, Kenya’s democracy has emerged out of a long history of colonialism and authoritarian rule, leading to a political economy that raises the stakes for elections and creates opportunities for violence. This is why all elections in the country are “high stakes affairs.”

Nicodemus Minde argues that a combination of issues such as the economy, integrity, and clientelism will determine the outcome. The climate, media, and misinformation could all be factors. John Githongo even worries that the election is about nothing. It is unclear whether the election will usher in any change.

Stay tuned to #KenyaDecides2022 #KenyaDecides. And follow these experts.

The Grand Hustle versus the Grand Finale is on.