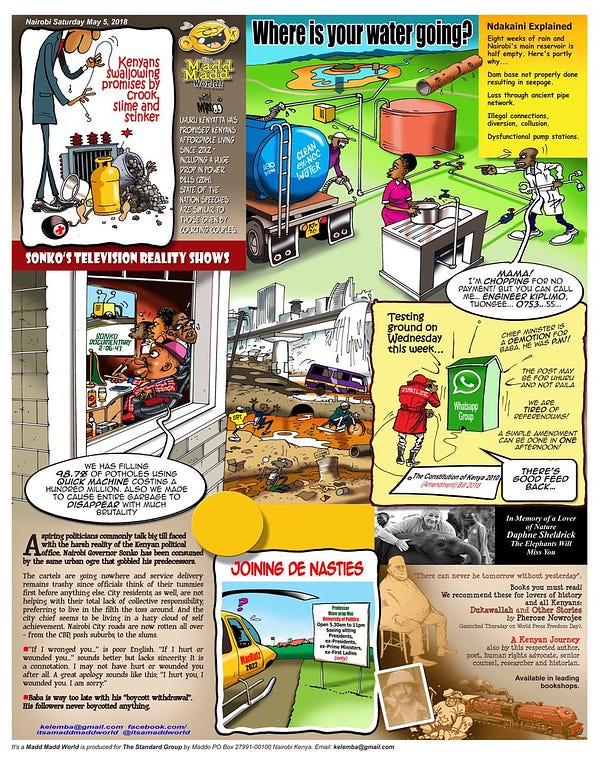

Opposition candidate Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu – aka Bobi Wine – in Uganda gets a lot of the attention (happy 40th birthday!), but the story of Mike Sonko’s rise and fall in Nairobi might be just as impactful.

Sonko was Governor of Nairobi County from 2017-2020, when he was impeached from office on corruption charges. The story of Mbuvi Gideon Kioko Mike Sonko, detailed by journalist Isaac Otidi Amuke in this excellent profile, highlights the challenges politicians face as they shift from building a political following to governing a city, especially in rapidly growing urban Africa.

Building a following

Sonko was born in Mombasa and came of age on the Southern coast, in Kwale. At age twenty, he was arrested for the first time, which set off a number of arrests which eventually led to his six-month sentence in 1997. After one month in prison, he skipped jail and found his way to Eastlands, Buru Buru in particular, a shopping center full of restaurants, pubs, and discotheques. As Amuke tells it:

Together with his wife Primrose, Mbuvi scrounged for capital and set up a hair salon, a barber shop, a video library, a cybercafe, an outlet for selling car parts and a clothes boutique. Being a fugitive, Mbuvi operated in the shadows. Primrose ran the show, and the businesses flourished. The couple opened a popular nightclub, then ventured into the matatus business.

After getting into trouble with the law again, another stint in prison, and an early release based on a questionable health record, Sonko eventually returned to Buru Buru where his matatu business thrived. Amuke continues:

Making it their main hustle, Mbuvi and Primrose accumulated a fleet of Nairobi’s loudest and most dashing nganyas, thereby dominating the Buru route. Money started streaming in by the bucket…Matatus made Mbuvi an el jefe – a boss. To run his ever-growing matatu empire, Mbuvi recruited some of the shrewdest youngsters across Eastlands to be his drivers, conductors and hangers-on, making him the leader of an influential network across Eastlands. It was in this era of Mbuvi’s life that he earned the nickname “Sonko”, which is sheng for boss or the monied one.

Sonko paired this hustle with flashiness – not to mention accusations of sorcery stemming from his upbringing on the Coast – with economic and political savviness. He was elected chairperson of the Eastlands matatu association, and defended them against the government’s desire to move the Eastlands matatu station. He built a cosmopolitan following that crossed ethnic and religious groups, incorporated young men and women into the matatu infrastructure, and provided the most important asset of all: jobs. He operated in cash, immediately jumpstarting a powerful election campaign for MP of Makadara Constituency in 2010.

On the surface, Sonko appeared to be simply buying votes, a key feature of political clientelism. But this misses the citizens’ perspectives. For many, Sonko provided an avenue for ordinary people to lay claim to the city. For others, choosing Sonko as a patron was the best possible option in such an unequal environment. At the very least, they finally saw one of their own represented in government. Sonko’s rise signaled a powerful form of social recognition – recognizing ordinary people as human beings deserving of dignity – and offered a potential transformative vision of Nairobi that it could be a city for them.

To learn more about the history of matatus, read Kenda Mutongi’s book.

Rising the political ranks

Sonko did not tone down his flashy and braggadocios antics as MP. As Amuke explains:

Personifying the name Sonko, Mbuvi dished out bundles of crisp currency notes indiscriminately to destitute Nairobians whenever they caught his eye or ear, conveniently broadcasting his generosity on social media. To keep the streets talking, he rose around town in gold-plated SUVs, wore kilos of gold jewellery and dyed his hair golden.

Sonko angered – and challenged – the political elite. Three months into his tenure, police raided his office and accused him of drug trafficking. He admitted to engaging in land fraud, which involved working with government officials to grab parcels of land leases that were about to expire and transferring those deeds to fraudsters who could then con buyers. But to protect against the drug trafficking charge and further government interference, he sought to climb the political ladder: he would run for Nairobi Senator, and align himself with one of the major political parties.

At this point, Presidential candidate Uhuru Kenyatta was facing charges at the ICC and needed support on the ground. Sonko offered this support – and mobilized his following to the cause. Sonko won the Senatorship in a landslide, but soon realized the true power lay in the Governorship. Nonetheless, he took matters into his own hands to further mobilize the grassroots, as Amuke documents:

He established a privately funded pro bono service-delivery entity known as the Sonko Rescue Team, which comprised of ambulances, fire engines and water bowsers. He enlisted the services of hundreds of youth to operationalise the entity, and asked them to pick up litter at the same time. He got the new organization to pay the medical bills of those needing specialized treatment in Kenya and abroad; and, in the unfortunate event of a passing-on, Mbuvi used his famous Buru nganyas as free hearses.

This brought him even closer to the president. His popular support was undeniable, and was a huge asset to Kenyatta and his Jubilee party. Sonko constantly boasted about having the President’s ear. He once called on Kenyatta to stop a demolition. He allegedly “put the President on loudspeaker,” and the crowd cheered when the President stopped the demolition.

In 2017 he ran for Governor, and he convinced Kenyatta to have his back. He staved off primary challenger Peter Kenneth – the establishment’s chosen candidate – and incumbent Evans Kidero in the General Election. But not before the establishment had their say: they insisted that corporate insider Polycarp Igathe be Deputy Governor to help govern. Sonko had made it: He was now Governor of Nairobi, with control of a large budget – and the largest city in Kenya.

Sonko’s rise illustrates how local power brokers can rise the ranks to power. In some ways, this confirms the results Noah Nathan and Sarah Brierley find in Ghana, that problem solving and upward ties to elites are most valuable to political parties as they seek to entrench power and win elections. But it also demonstrates the importance of class politics in urban Africa – as I have written about in the context of Ghana – as populist candidates turn to protecting the poor against property developers and corrupt bureaucrats.

Competition and political control

Sonko packed City Hall with a loyal following from his days in Eastlands. They were unqualified for office, and everything went through Sonko. Igathe could not make a mark, so he resigned after six months. Sonko constantly shuffled his cabinet, instilling a culture of fear. The civil servants and businessmen – considered the establishment – tried many things to curtail Sonko’s grip on power, but were constantly pushed back.

But Sonko finally went too far. His supporters attacked Nairobi businessman Timothy Muriuki, assaulting him publicly. It was humiliating and a public embarrassment, and spread on social media. Amuke explains:

[The establishment’s] next attempt used Mbuvi’s paranoia. Fearing that City Hall was bugged, Mbuvi oscillated the running of Nairobi’s affairs between a nondescript pied-a-terre in the city’s Upper Hill area – which he converted into a personal office – and his gigantic hilltop Mua Hills mansion filled with in-your-face gold furnishings, located in the outskirts of Nairobi.

Sonko ran City Hall more and more like a mafia boss, and the agency was going broke. This is when the anti-corruption agency struck, alleging money-laundering and corruption. Perhaps the real crime was political: He aligned himself with William Ruto, who had recently fallen out with Kenyatta. Sonko was part of the wrong alliance.

But the way the national government re-established political control in Nairobi is also telling: Kenyatta created the extra-constitutional Nairobi Metropolitan Services and appointed General Mohamed Badi to lead it. He claimed that Sonko had failed to govern the city. This intervention is part of a longer set of power grabs by the national government, as Gideon Ngumbau outlines in his piece.

Nairobi County with an elected governor still existed, but it lost its funding and had little authority. This led to a power struggle between the two agencies over governance in the city. Sonko was later impeached. Meanwhile, Badi tightened his grip on power, which included overseeing numerous demolitions across the city in the “name of development.” It also signaled the political establishments desire to keep Nairobi a space for the elite.

Several years ago, Museveni used a similar tactic in neighboring Kampala, when he centralized authority in the city by establishing Kampala City Council Authority. But successful metropolitan governance can also threaten those in power, as KCCA executive director Jennifer Musisi found out years later, and Freetown mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr is experiencing today.

National governments are turning to urban capture and control in capital cities as a new form of political dominance. How candidates and opposition parties respond in its largest cities is at the forefront of contentious battles in African politics.

The future of urban governance

Mike Sonko is a unique character. But he also serves as a model for a type of politician we might see across Africa as the youthful continent urbanizes. Sonko’s path to power sheds light on political mobilization and governance in African cities, including:

The ability to mobilize a cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic coalition of supporters.

The importance of cash-based businesses to fund electoral campaigns.

The capacity to solve peoples’ problems.

The power of a well-organized network of associational and occupational groups that can easily be mobilized and called upon in times of need.

The strength of having the ear of the President, especially his mobile number on speed dial.

The development of an anti-elite and anti-government populist narrative.

The political tensions that underlie multi-level governance.

While Sonko might be down now, don’t count him out.