In a recent GLD Working Paper, Steven Brooke and Monica Komer explain how mosques can be important spaces for women to resolve personal and community issues. Examining the role of Mosques in Tunisian society, they find that women are more likely to turn to mosques for non-religious purposes in marginalized areas, where women have limited opportunities to access alternative spaces for these services. The implication is clear: in many societies, individuals must be creative about how and where they participate in civic life.

Check out the one-page GLD Policy Brief that summarizes the key findings.

Spaces of politics

My advisor in graduate school, Michael Schatzberg, always pushed his students to expand the boundaries of the political. He saw politics in family and food. And beer and football. These spheres of daily life shape what people deem legitimate – or thinkable. These everyday metaphors help explain how people understand their political universe. They can also highlight why and where policy reform fails.

Schatzberg’s 1982 article is still relevant today. In this article, he explains why Zaire’s attempt to create a uniform and centralized administration – by abolishing the collectivites locales comprising chieftaincies and sectors – failed. The national government attempted to bring local chiefs under the jurisdiction of the state. He writes:

“The state therefore brought collectivity chiefs into a highly centralized national administrative system by making their tenure directly dependent upon the central power in Kinshasa. The chiefs, especially those in the former chieftaincies, were no longer seen as representatives of traditional, customary authority” (338).

Chiefs would lose their financial autonomy. Moreover, the state had trouble in implementation: they could not figure out who was really a chief.

“The question of who was, or was not, a hereditary, traditional chief proved particularly vexing… These instructions, like so many others from the central authorities, were not clear to those in the hinterland with primary responsibility for implementing them… confusion abounded at all levels of the administrative hierarchy” (341).

In the end, these policies were out of touch with the daily realities of local governance. Schatzberg points to “ad hoc policy formulation, incoherent policy pronouncements, and lack of attention to the concrete problems of policy implementation” (348) as factors for why the policy reform failed. Clearly, authorities were not paying attention to the local spaces of politics where decisions are actually made and policies implemented.

Vibrant arenas of political life

These non-state spaces are vibrant arenas of political life. Like mosques, they can be places where residents engage in collective action and decision-making. They can also be important sites of political accountability. I’ve written about this in the context of urban Ghana.

There are many examples across the world. In Chinese villages, community solidary groups hold politicians accountable through informal rules and norms that require leaders to demonstrate a high moral standing in the community. In India, residents turn to NGOs, village councils, and political brokers, to pressure the state for social services. In Argentina, residents of shantytowns form personal problem-solving networks with brokers and community leaders and use festivals and social events to demand public services. In Botswana, citizens join traditional public assemblies called kgotlas to legitimate the authority of their leaders and get their voices heard. In Kenya, residents join street parliaments (or people’s parliaments) to discuss politics and claim belonging in the polity.

Non-state spaces are important sites of political participation.

Beyond the NGO

Policymakers often reduce the space between the market and the state to civil society. In international development, NGOs typically fill this space.

I’m often critical of NGOs, and their official duties for being out of touch with local realities. They often distort the local political economy and have their own underlying political dynamics that are masked in a technocratic or apolitical veil. But the work of Julia Elyachar and others outline how communities can creatively make NGOs their own. There are multiple forms of power at the intersections of the state, international organizations, and NGOs. Communities on the ground operate in these complex relationships of power and carve a path forward.

NGOs can open up new spaces of political engagement for ordinary residents. They can be especially important for women and marginalized social groups. But the informal activity – rather than the official mandates – sometimes mean just as much for residents on the ground. Take this example from my book:

“On a quiet morning in January, a group of Ashaiman women from different ethnic groups met at a USAID-funded health clinic. But the women were not meeting to discuss health concerns, nor did they come to talk about the NGO’s agenda. Instead, they came to discuss problems in the community, as they did every Tuesday morning. They used the space paid for by USAID to gather and talk. Immediately, the women started complaining about the public toilet. It was not cared for, was very dirty, and they had to pay ten peswas for their young children to use it. They felt that this was not fair. They did not like that the proceeds go to the NDC party, and most of the money goes directly to the assemblyman… The women’s group creatively recombined their role as health workers – and the materials and office for which USAID expected health work – for general improvements in the community” (216).

A good place for all policymakers to start is to ask: Where do people make community decisions in everyday life? Sometimes NGO offices play a meaningful role. They can even blur the boundaries between state and society. In the case of Tunisia, mosques serve this purpose.

Religion and politics

There is excellent new research examining the relationship between religion and politics. Gwyneth McClendon and Rachel Riedl’s From Pews to Politics: Religious Sermons and Political Participation in Africa examines how religious teachings can influence the degree and form of political activity. Amaney Jamal’s work has long examined the role of mosque activity on political consciousness. But most of this work focuses on formal political participation, like voting behavior and partisan identification.

Equally as important, if not more, is the role that houses of worship play in everyday life. Importantly, as anthropologists like Deborah Pellow have contended, they contribute to collective decision-making and claim-making. Brooke and Komer’s study deepens our understanding by clarifying where houses of worship facilitate local governance.

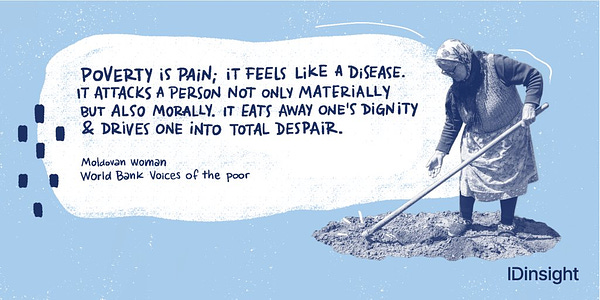

Governance beyond the state

This focus on governance beyond the state contributes to an exciting new policy agenda. I am excited to see how foundations like the Hewlett Foundation – who just announced a new women’s empowerment initiative and a re-vamped Transparency, Participation, and Accountability strategy – and organizations like ID Insight (with Dignity Initiatives and others) incorporate this sphere of decision-making into their projects.

GLD is always looking for spaces of governance beyond the state. We highlight citizen experiences – the activities, behaviors, and attitudes of ordinary people in their own neighborhoods and villages. Expanding the political has long been a frontier of social science research. It now deserves a central place in policymaking.