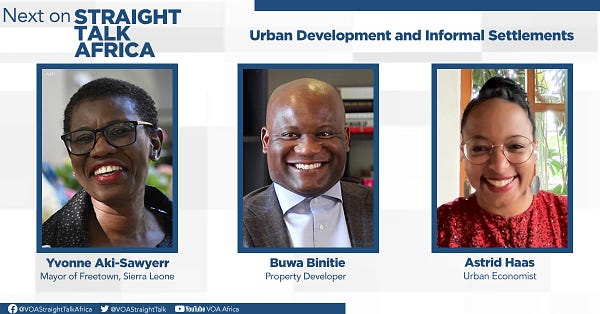

In a recent segment on VOA’s Straight Talk Africa, Freetown Mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr makes a strong case for more urban planning on the continent. “What I think is underemphasized, doesn’t get enough airtime, doesn’t get enough funding, doesn’t get enough attention,” she says, “is urban planning.” She worries about a future where “we continue to grow in this uncontrolled manner.”

She then highlights the different ways that cities are run. She explains that the president appoints mayors in Accra and Monrovia, while citizens elect mayors in Sierra Leone. Still, she says that “mandates of cities” remain unclear. She seems to suggest that comprehensive urban plans can clarify city mandates. A fair and inclusive planning process – a newer, more innovative type of planning – might be able to solve these larger societal challenges, and put cities on a path toward a sustainable future.

But urban planning might not be enough.

Aki-Sawyerr’s interview offers important insights about African cities, and how they should be governed. Plus, she is actually doing the work. But it also raises more fundamental questions that require political solutions: What are African cities for? And for whom?

The entire episode – which also includes an important conversation with economist Astrid Haas – is well worth a watch.

1. The politics of urban governance

An inclusive planning process is a lofty goal, but it is not a technocratic exercise. Nor is it something that international organizations can simply inscribe on a local population. It requires more than a Ted Talk.

This is because citizens and elites cannot agree on what cities are for – and for whom. This is not an “Africa problem” but rather a challenge across the globe. But in Africa this challenge is at the forefront of the entire sustainable development agenda. Cities like Lagos, Johannesburg, Nairobi, and Kinshasa have bigger economies than many countries. Cities are engines of growth for entire countries, and can be at the forefront of modernization campaigns by the national government. The grand ambitions of national governments often conflict with desires of local residents and realities on the ground.

Take the example of Addis Ababa, which Ezana Weldeghebrael wrote about recently in The Conversation and the ACRC Scoping Study. He writes,

“Even though residents elect the city council, they don’t have much say. Urban planning processes tend to be expert-led –- for instance, the 10-year structural plan (2017-2027) which was effected to guide the development of the city. However, due to constant city leadership changes, imposition of modernist urban models, and corruption, it’s common to find developments that violate the urban plans. These include government projects.”

The city has made infrastructural investments. Poverty and unemployment decreased. Yet most of the developments feature luxury real estate projects and tourism schemes. Biruk Terrefe argues that “there is a new urban aesthetic emerging in Addis Ababa targeting domestic elites, the Ethiopian diaspora and tourists.”

But the city is overlooking the needs of the poor. Many argue that it is also turning its back on the Oromo people, who claim indigeneity and belonging to Addis Ababa. The expansion of the city continues to displace Oromo farmers. Opponents are clear: This is how not to make a master plan for the city.

2. How African cities are run

In a recent article, I suggest that we need to pay more attention to the everyday politics of cities and their neighborhoods. Everyday urban politics is “the institutional context of daily decision-making in a neighborhood – how people act, think, and feel about power on a daily basis.” Urban planning must incorporate “the issues and concerns that urban residents consider most important in their daily lives.”

While residents sometimes want grand megaprojects, they often just want access to basic services and jobs. But many times, poor and rich residents alike make claims to indigeneity, first-settler status, and territorial control that are exclusionary and restrictive to migrants and outsiders. Urban governance evolves into a host-outsider struggle over who really belongs in the city. Party politics exacerbates these underlying tensions.

Central to these power struggles is political clientelism, which also shapes the planning process. Chandan Deuskar explains:

“The urban poor lack the resources to engage in corruption on a large scale, but in democracies, they do have votes, and so they engage in clientelism to negotiate for access to land and services.”

This informal provision of land and services can get in the way of formal plans and undermine the creation of cities that benefit all residents rather than just a narrow slice of the population. Deuskar even finds a statistical correlation between informal urbanization and clientelism.

3. A new approach to planning

Of course, African cities need more urban planning. Every city in the world could use more planning. But it needs the right kind of planning. Randolph and Deuskar advocate an approach for smaller cities that is more like “barefoot planning,” which “would provide training in basic planning-related skills to a cohort of citizens in small towns and cities, empowering them to perform some roles traditionally reserved for professional planners.” This is worth considering.

The ACRC recommends citizen-government coalitions.

Kaiping Chen finds that deliberative polling can empower citizen voices. Taibat Lawanson and her colleagues argue that a neoliberal economic logic in Lagos is undermining the intents of the city’s development plan. This highlights the shortcomings of urban planning if social factors are not integrated into the governing process. Recent demolitions in the city demonstrate how powerless plans can be if the government defies the orders of the courts.

Barefoot planning, citizen-government reform coalitions, deliberative exercises, or social welfare mechanisms might provide the answers, but everyday politics underlies them all. They are fraught with their own internal politicking that can undermine the planning process—especially implementation. One planning exercise might work well in one local context, but a very different one might be required in another.

Building better cities of tomorrow takes careful planning – but also understanding the political processes that shape prospects for a sustainable urban future.