Ghanaians go to the polls on Saturday, December 7 to elect a new president in one of the final African elections of the year. Across the continent, citizens view democracy as failing to provide a better life for them which is leading to declining satisfaction in democracy. Ghana is no different: Ghanaians are not happy. Nonetheless, democracy has remained resilient thus far and Ghana’s election is likely to continue this trend.

Current vice president and New Patriotic Party (NPP) presidential candidate Mahamudu Bawumia faces an uphill battle as it is clearly not the year where there is an incumbent advantage. He focuses his campaign on providing #BoldSolutionsForTheFuture. Former president and National Democratic Congress (NDC) candidate John Mahama positions himself as the change candidate with the goal of #ResettingGhana.

H. Kwasi Prempeh outlines what is at stake. Nelson Oppong explains how the polls will test the pulse of the country’s democracy. It is also a test for the West Africa. IFES provides this snapshot of the race. Bloomberg discusses what the economic impacts might be. An additional wrinkle is the spread of disinformation on social media.

Urban middle classes tried to make illegal mining – locally called galamsey – a central campaign issue in this year’s election. The practice of artisanal mining has drawn widespread scorn from the electorate, but the candidates have been unable to articulate a clear plan forward. 60 percent of Ghana’s fresh water source is contaminated by the practice.

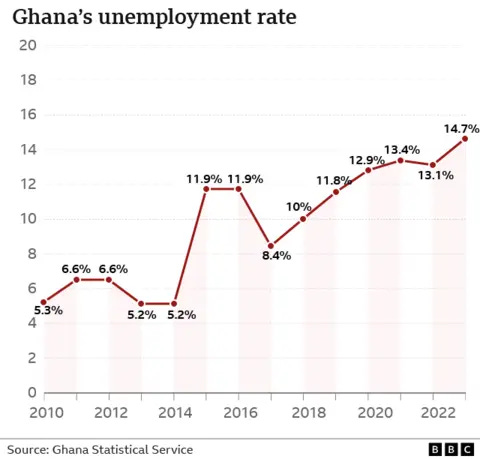

But what is mostly on the minds of voters? Economic hardships. Fertilizer subsidies and the high cost of living are major concerns to voters. As always, Theo Acheampong reminds us that it’s the economy, stupid.

The candidates

NPP’s flagbearer Mahamudu Bawumia is running a forward-thinking campaign that rests on further integrating Ghana into the global economy. The NPP’s manifesto focuses on creating jobs and supporting business, emphasizing food security and irrigation; advancing technology and improving market access for farmers; increasing digitization through the Ghana Card and improvements in mobile money; supporting innovation in procurement, and; investing in new mining practices.

NDC’s flagbearer John Mahama continues his long pursuit to return to the state house. He emphasizes a 24-hour economy that will create jobs for Ghana’s youth. He seeks to clean up the “NPP’s mess.”

Third party candidates Nana Kwame Bediako and Alan Kyerematen look to act as spoilers and it is unclear what impact they might have on the outcome.

Balance of power

Ghana’s two-party system has its roots in the fight for independence, where the founding president Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP) split from the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) in 1949 over the speed and tactics used to overcome British colonial rule. The contemporary manifestation of the CPP and UGCC – the NDC and the NPP, respectively – dominate competitive politics today.

The NDC has long relied on support at the grassroots, including unemployed youth, unions, occupational groups, and ex-servicemen. The NPP derives its support from the Ashanti Region, home of the largest ethnic group in Ghana. The Ashanti region benefits from gold deposits and a productive cocoa industry, and takes great pride in its hierarchical governance structure with the Asantehene at the center. Dating back to precolonial times, the Asante accumulated wealth and created an elite class of Asante nationalists whose historical legacy persists and descendants form much of the power base of the NPP today.

This history has led to deep historical grievances between groups that get politicized during election time. Political parties exploit local divisions, many of which draw on long-standing disputes over claims to land and territory. In turn, local leaders use political parties and elections to advance their own personal agendas.

Organized uncertainty

Elections are now extremely competitive affairs that deliver a modicum of accountability by throwing out representatives who do not deliver. Perhaps just as importantly, elites from both parties have benefitted from state power since 2001. Citizens, in turn, demand elections as a way to get their voices heard and gain access to public services.

An independent electoral commission and judiciary have helped insulate the electoral process from partisan politics, although there is some worry that the governing party has infiltrated these bodies with partisans. The Afrobarometer reports that only 33 percent of Ghanaians trust the electoral commission, the lowest in two decades.

Elections continue to offer Ghanaians a space to dissent government policy and exercise their political voice. While there remains persistent corruption and vote-buying, the NDC and NPP offer selective incentives for survival and the opportunity to be recognized by politicians and the state. These parties play a central role in organizing politics and brokering state-society relationships, ensuring a moderate level of political competition.

The biggest threat to Ghana’s democracy might be its greatest strength: the dominance of its two-party system. Some analysts worry that its political parties have become too powerful and get in the way of meaningful dialogue and programmatic politics. In addition, Ghana has failed to move beyond electioneering to safeguard minority rights, curb executive power, and protect media freedoms.

Political campaigns in Ghana

Political campaigns are a chance for politicians to communicate their messages directly to their audience and for supporters to listen and take part in the democratic process. In a recent article, George Bob-Milliar and I explain how politicians use campaign visits – which include official business stops, courtesy calls to local notables, and personal interactions with constituents – to interact with as many citizens as possible.

We document a rise in campaign stops from the 2016 to 2020, from 317 to 539. This demonstrates how politicians have learned that these stops are powerful ways to connect with constituents and shape a narrative. These stops are even more important in 2024, as Bawumia draws from government funds to celebrate the commissioning of projects, while Mahama is no longer limited by the COVID restrictions of 2020.

Bawumia explains the logic in a recent post on Facebook:

“Over the past 17 months I have visited every single Constituency in Ghana, listening to the concerns and aspirations of our people, and sharing my vision for Ghana’s bold, new future. I have engaged traditional authorities, religious leaders, Identifiable Groups including the youth and ordinary persons in their homes, markets, lorry stations, places of worship and in the streets, exchanging ideas and showing why I am the best option to make Ghana’s desire for greatness a reality.”

Ashanti and Greater Accra are campaign kingmakers

With growing populations, the metropolitan areas of Accra and Kumasi are increasingly important. Mahama is spending more time in the Ashanti Region, a stronghold for the NPP, while Greater Accra has become a very competitive swing region. As a party activist notes, “Power passes through Kumasi to Accra.”

Mahama and Bawumia are also visiting the far reaches of the country, including the northern regions where they both grew up. Bawumia is taking credit for helping resolve the Dagbon crisis, while Mahama attempts to build on the legacy of Jerry John Rawlings by “opening up the north.” The entire country is in play, especially because the control of Parliament is also up for grabs.

The re-emergence of traditional authorities

While both major parties have hired PR firms and management consultants to professionalize their campaigns, they are increasingly reliant on campaign visits to directly engage with their supporters at the grassroots. Candidates are visiting traditional authorities in their own districts far more than they have in past campaigns. Traditional leaders are seen as partners in the democratic process. As Mahama notes during his visit to the Ga Mantse:

“I have always believed empowering traditional leaders to take a more active role in governance can create a more inclusive and effective system honouring our cultural roots. I am committed to enhancing relations with our chiefs as we move forward. They are not only custodians of our traditions but also key stakeholders in our development agenda.”

Similarly, Sarah Brierley and George Ofosu find that chiefs’ endorsements can significantly impact the vote choice of undecided voters, as well as increase voters’ perceptions of quality performance.

Anti-LGBTQ Bill

Political parties are stoking anti-LGBTQ sentiment after Parliament passed a punitive anti-LGBTQ+ bill in February. Many Ghanaians are afraid for their future. The bill is extremely popular with Ghanaians, but critics warn that it violates human rights and Ghana’s own constitution. After extreme pressure, Bawumia said he will sign the bill into law if elected. Mahama has said homosexuality is against his Christian beliefs.

Critics worry of “continental contagion.” Anti-gay legislation is being considered in Kenya, Namibia, Tanzania, and South Sudan. The impact of anti-gay legislation in places like Uganda is already being felt, as community health clinics cannot support its patients, exacerbating health problems. Amnesty International reports that LGBTQ+ people face fear, attacks, increased oppression, and growing hostility towards their identities.

While Ghana’s electoral democracy will likely prevail, the rights of many of its citizens still need to the protection of the law. The winner of Ghana’s election will play an important role in protecting individual rights and freedoms.